This year Superman turns 75, and what better way to celebrate than with the release of a new movie adaptation of his heroic exploits? The lukewarm critical and commercial reception which greeted Bryan Singer’s Superman Returns in 2006 caused many to question whether another attempt would ever be made to bring the character back to the big screen, and whether in a post-Dark Knight world of gritty superheroic realism there was actually any place for a such an unashamedly technicolor hero as Superman. Despite this, Zack Snyder’s cinematic reboot, Man of Steel, is due to open in cinemas this June, seven years to the month since Superman Returns was released. Unlike Singer’s film, Man of Steel will be a retelling of Superman’s origins, and will attempt to build an entirely new – albeit familiar – cinematic identity for the last son of Krypton. But there is widespread apprehension about how the film will actually depict Superman, and not merely because of the perceived poor showing of its Hollywood predecessors. Simply put, Superman is very difficult to get right, arguably more so than any other A-list superhero. Although Man of Steel‘s latest eye-popping trailer has assuaged this concern somewhat, worries still remain about Zack Snyder’s approach to adapting this cultural icon for the big screen.

Why should this be so? After all, the basic concept of Superman is so simple that Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely were able to sum it up with just four panels and a splash page in their beautifully constructed comic All-Star Superman (of which more later). Why should such an uncomplicated story be so difficult to tell well? There are two answers to this question, namely the inherently mythic nature of Superman, and the current realist paradigm in 21st century superhero cinema.

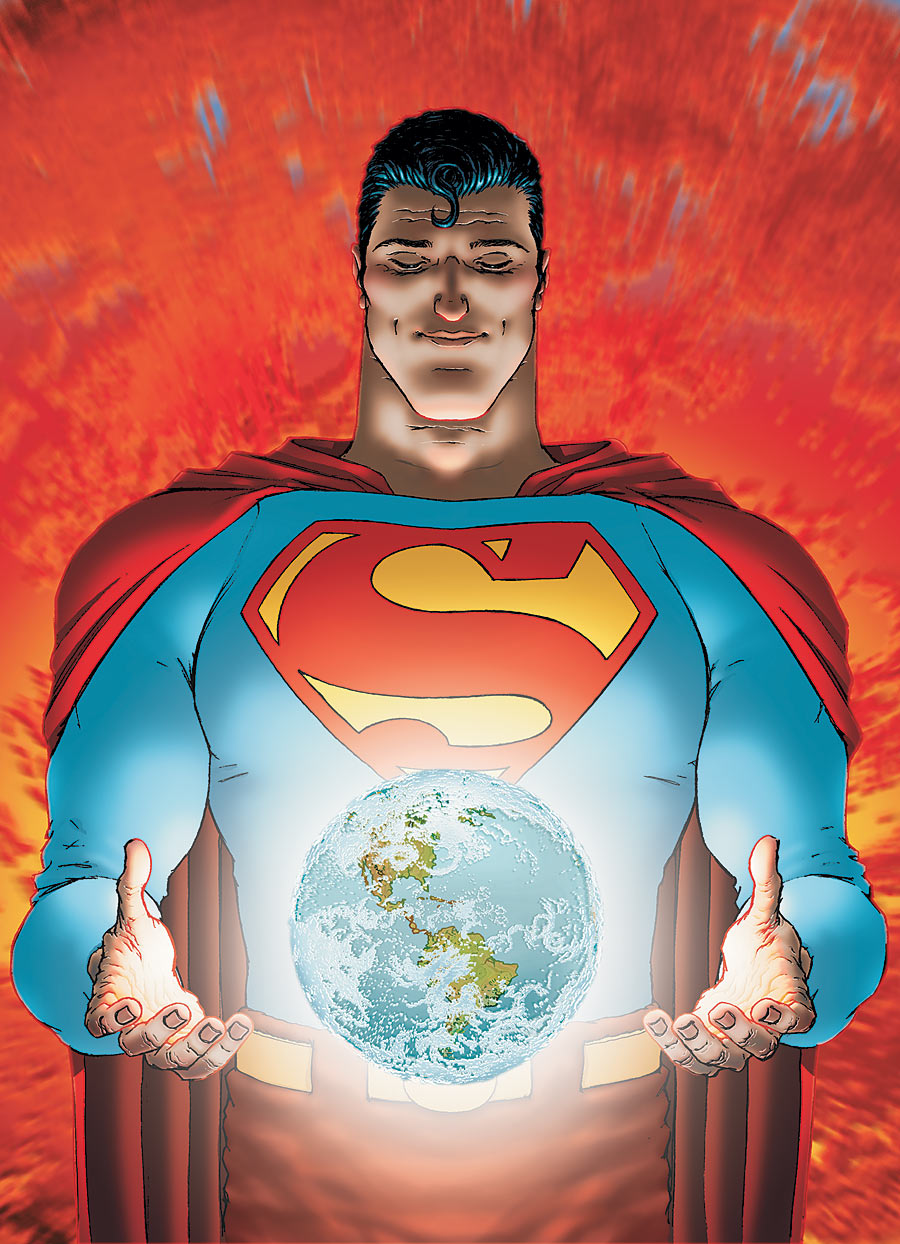

Celebrated comics author Grant Morrison writes extensively in his book Supergods about the mythic quality of superheroes, and the fact that they should rightly be understood as the successors to ancient Greek characters like Hercules and Perseus, rather than the military heroes and science-fiction adventurers who preceded them as comic strip icons. This mythic status, he argues, is particularly true of Superman, the archetypical superhero. However one interprets the Man of Steel, be it as an allegory for the Jewish diaspora or a Christ-like role model for human morality, his uncomplicated do-gooding and nebulous super-powers place him squarely in the mold of the mythical heroes from antiquity, as opposed to, say, the more obviously science-fiction realm of other DC characters like Green Lantern and Martian Manhunter, as well as many Marvel heroes like Iron Man, the Incredible Hulk and Captain America. The reason that Morrison’s aforementioned mini-series All-Star Superman is arguably the best Superman comic ever written is that this mythic quality is right at the heart of its depiction of the character. There is no post-Watchmen attempt to drag an emphatically fantastical hero kicking and screaming into reality; rather, the comic basks in the sheer unreality of its central concept.

A common criticism levelled at Superman by fans of more mundane superhero characters is that he is simply too powerful, and that since activities as prosaic as stopping crime and fighting supervillains are no challenge to him, they do not generate dramatic tension. In a way, this criticism is a valid one, but it is a mistake to think that the problem lies with the character of Superman, rather than the challenges with which generations of comics writers have traditionally presented him. Morrison realised that the best possible way to portray Superman was as a modern myth; a primary-coloured titan undertaking Herculean, galaxy-spanning labours which befitted his stature. He demonstrated that having a central character possessed of such god-like power is no barrier to great story-telling, provided that you place him in the correct context. Such a character is also suited to the epic spectacle of short-form, ‘event’ storytelling – as the lean twelve-issue length of All-Star Superman suggests – rather than the long-form, never-ending story-lines of most comic books, which are always in danger of making the mythical mundane. This being the case, concise, two-hour chunks of film seem like the ideal medium for properly rendering the mythic tale of Superman, provided that they also contain the appropriate level of visual spectacle. Why then should there be such apprehension about this latest attempt to adapt Superman for the big screen?

Hollywood’s penchant for gritty realism in superhero films arguably began with Stephen Norrington’s Blade and Bryan Singer’s X-Men, but it was compounded by the success of two superhero franchises which were dominated by such an aesthetic; Jon Favreau’s Iron Man films and – in particular – Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy. Zack Snyder is very much a director for these times, as even a cursory glance at his oeuvre will confirm. The success of 300 and Watchmen have made him a prime candidate for realising comic book properties in this age of dark, cynical blockbusters, where the primary colours of yesterday’s superheroes have been dulled to a grey pallor. This is not to say that such an approach hasn’t reaped artistic dividends for certain characters; Nolan’s take on Batman has been nothing short of a critical triumph, and despite its apparent lightheartedness, Joss Whedon’s Avengers Assemble would have been a much lesser film without a darker heart beating beneath its veneer of colourful irony. It’s tempting to assume that what’s good for the super-goose is good for the super-gander, and early publicity stills from Snyder’s Man of Steel which emphasised a darker take on a classic story suggested that this virulent strain of grit and cynicism would be bringing a new lease of life to Superman’s cinematic incarnation. But it is a fundamental mistake to assume that, just because Superman occasionally shares a comic with Batman, what brought out the best in the latter’s character will do the same for the former in the context of a movie adaptation.

Dragging an inherently mythical creation into a world of gritty realism only serves to lessen it, and any attempt to adapt Superman in such a way will not only fail to revitalise the franchise, but will also confirm cynics’ suspicions that the character is irredeemably out of touch, and belongs solely to a bygone era when superheroes were uncomplicated and ironic self-awareness was not a prerequisite for storytelling. A mythical character needs to be placed in a mythical context, which means creating a film that eschews the dominant fashion for darkness, cynicism and irony in superhero movies. Superman is meant to be a symbol, representing the very best that humanity can aspire to be in a character who isn’t even human himself. Grant Morrison’s suggestion that Superman should be portrayed “a bit like Jesus” is perhaps not so very wide of the mark. We can only hope that Zack Snyder, Christopher Nolan (producing) and David S. Goyer (the film’s writer) will have been brave enough to produce a movie which bucks the current trend of superhero cinema, and doesn’t darken its hero to the point where those primary colours are no longer visible. The latest trailer for Man of Steel gives us some hope that this might be the case after all, with its promise of epic spectacle tempered by sincere sentimentality. But only time will tell if, 75 years after his first appearance in Action Comics, the modern myth of Superman can survive the cynicism of the 21st century.

[…] right way to bring Superman back to the big screen was never going to be easy (as we discussed in a recent article), and while Man of Steel is far from the train wreck that many feared it would be, the film has a […]