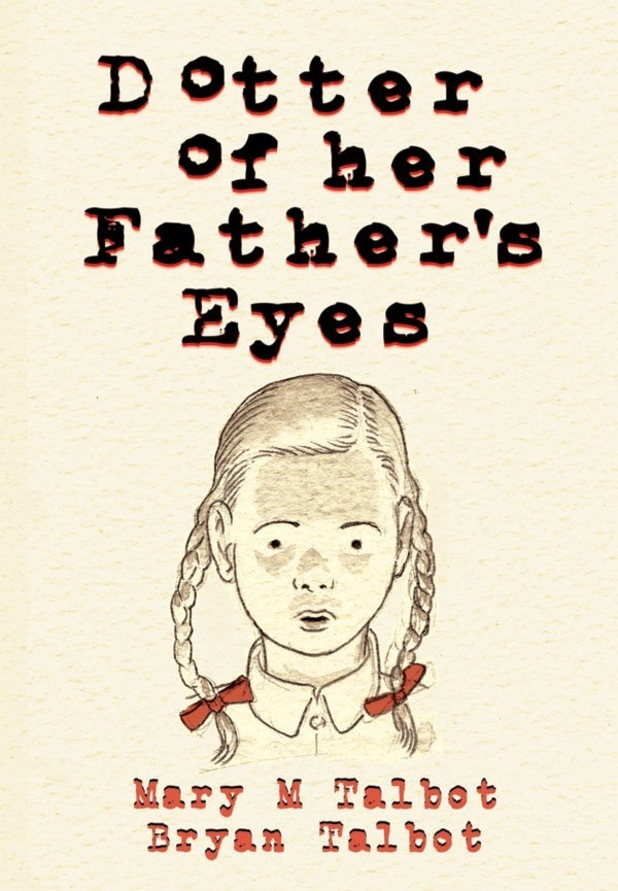

The 2013 Edinburgh International Book Festival starts in 4 days’ time (Geekzine coverage will begin shortly), and one of the themes of this year’s programme is ‘Stripped‘, a celebration of graphic novels (or comics, as they used to be called). It might seem unusual, given the traditional snobbery of the literary establishment, for comic books as a medium to feature so prominently at one of the country’s biggest book festivals, but this is actually part of a recent trend in the world of literature that has seen comics “come in from the cold”. Slowly but surely, comic books are gaining a modicum of respectability within the literary establishment, a gradual shift which some would argue dates back to 2005, when Time magazine named Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen as one the 100 greatest novels in the English language. I’m not convinced that this was quite the paradigm shift many hold it up to be (acclaim for one “graphic novel” does not lend legitimacy to the entire medium – indeed, it can be considered the exception that proves the rule), but it was perhaps nonetheless a harbinger of things to come. Recent years have seen celebrated prose authors such as Ian Rankin, China Mieville and Jodi Picoult make the transition (albeit a temporary one) to scripting comic books, and the triumph of Mary and Bryan Talbot’s graphic biography Dotter of Her Father’s Eyes at last year’s Costa Book Awards seems to confirm that sequential art storytelling is now finally being recognised as a ‘serious’ literary art-form by the movers and shakers of the book world. Those of us who have always loved comic books are encouraged to take heart in this change of fortunes, but while it’s nice to see the writers and artists who work in the medium receiving more widespread acclaim for their efforts, I can’t help but feel that there’s something wrong with this picture. Why? Because comics are not books.

A comic book works completely differently from a novel. True, both have dialogue (usually), and both will employ some amount of narration (usually), but comics are primarily works of pictorial art, rather than an attempt to paint pictures with words. Anyone who has ever seen pages from a comic script (i.e. what the writer actually writes and then sends to the artist) will know that this form of writing arguably has more in common with screenwriting for movies and TV shows than it does with the work of prose authors. In the film world, the words of the script are realised through the use of cameras, actors and special effects, whereas in comic books, the script is brought to life through the efforts of the artist. Although sometimes the writer and the artist are the same person, the process of creating a comic book (and reading it) is completely different from the writing (and reading) of a novel or non-fiction book. There are things you can do in one art-form that you simply cannot do in the other; both have their strengths and their limitations, and these are what separate them as mediums. Both tells stories, both are printed on paper (usually) and both are stocked in bookshops, but this is where their similarities end. Recognising this fact has major implications for how comics should treated in comparison with books.

Comic books have always been respected as an art-form in countries like France and Japan, but mainstream critics in the English-speaking world seem to have a particular problem with taking the medium on its own merits. Treating comics as a subset of books for the purposes of literary reviews and awards has become the only way that these critics can bring themselves to acknowledge their existence, even though this diminishes the medium as an art-form in its own right. This is why graphic works like Dotter of Her Father’s Eyes are strangely being shortlisted for literary prizes alongside works of prose, even when judging two different forms of art for the same prize seems faintly ludicrous. It is also why the term “graphic novel” has now become the preferred designation for comic books, even in geekier circles. The use of the term “novel” is thought to lend the medium respectability because of its literary connotations, and as such is used by fans to aggrandise their passion, and by critics to make their subject more acceptable to literary peers.

There seems to be a great deal of confusion over how the term “graphic novel” should actually be used. It is not simply an invention of the literary establishment, or of comics readers desperately seeking credibility, but is a legitimate description of one particular form of comic book. There are in fact three such forms, each with their own designation:

Single issues (or “comics”) – These are the slim, individual issues that you can usually only find in dedicated comic shops. They tend to be published on a monthly basis, and – outside of newspaper strips – are the original form of comic books. Although “comics” is my preferred catch-all term for the medium as a whole, it can also be used to refer to this particular form.

Collected editions (or “trades”) – These make up the bulk of comics that are sold in bookshops. They are collections of previously published single issues, grouped together by story arcs or a writer’s/artist’s run on the title. Each collection will typically feature anything from three to twelve issues of a title, although there are also omnibus editions which collect dozens of issues in a single hardback or paperback form.

Graphic novels – The proper use of the term refers to those collection-sized hardback and paperback comic books whose content was not previously published as individual issues. They are wholly original, long-form works.

Most comic books that are referred to as “graphic novels” are in fact collected editions. Moore and Gibbons’ Watchmen, Neil Gaiman’s Sandman and Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns were all originally published as single issues, meaning that calling their collected editions “graphic novels” is technically erroneous. Only those works originally published in a longer format, such as Bryan Talbot’s Grandville and Craig Thompson’s Blankets, really qualify as “graphic novels” in the true sense. Any attempt to stretch the term beyond this application smacks of striving for faux-acceptability, when comics really shouldn’t have to try to impress the world of literature at all.

Saying that comics and books are separate art-forms does not imply a hierarchy; neither is a more ‘worthy’ pursuit than the other. The fact that comics have to sneak into respectability by disguising themselves as books in award shortlists and review columns flies in the face of this notion, and devalues the medium as a whole. Comics are a legitimate art-form in their own right, and need to be recognised as such, rather than being thought of simply as an offshoot of prose writing. Only when this happens can comics truly be said to have become respected in their own right.