“We always write in order to remember the truth. When we invent, it is only in order to remember the truth more exactly.” (Luis Fernando Verissimo)

I’ve often mistakenly attributed the above quote to Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges, possibly because it’s written in a book (Borges and the Eternal Orangutans) which pays tribute to the master short story-writer. But despite my foggy recollection of its origin, it’s become one of my favourite quotes, partly because it’s now my go-to riposte when arguing with people who say that science fiction (in particular) doesn’t have anything to say about the real world.

Poncey literary ruminations come easily to someone who works in a bookshop, which is where I was when I encountered the customer who unknowingly provided the inspiration for this article. The gentleman in question was looking for a novel for his grandson, and specified that it had to be something different from the usual science fiction and fantasy which the boy preferred, because he wanted him to read something which was “about the real world for a change”. I found myself uncomfortable with this idea, not only because a realistic setting does not necessarily a good book make (obviously), but also because my mind’s immediate (unspoken) response was: “of course science fiction can be about the real world!”

Snowpiercer

By definition, works of science fiction do not take the “real world” as their setting, but this doesn’t mean that the stories they tell don’t resonate with readers and viewers in the course of their day-to-day lives. Having a futuristic or fantastical setting doesn’t preclude a book or film connecting with its audience emotionally, and such a connection often occurs precisely because the work tackles an idea or theme which stands out as being relevant in some way to the “real world” which that audience inhabits. In particular, there’s a rich heritage of allegory in science fiction, and various books, films and TV shows in the genre have portrayed events and characters which echo situations and people in the real world. The latest high profile addition to this list is director Bong Joon-ho’s dystopian thriller Snowpiercer (based on the french comic book of the same name), which portrays the last remnants of humanity living together on a monstrous train, with the rich living in luxury at the front and the poor in squalor at the back. It’s an obvious metaphor for class hierarchy on a global scale, and the social unrest which such inequalities inevitably generate, and thus follows in the footsteps of many of its socially-aware SF forebears.

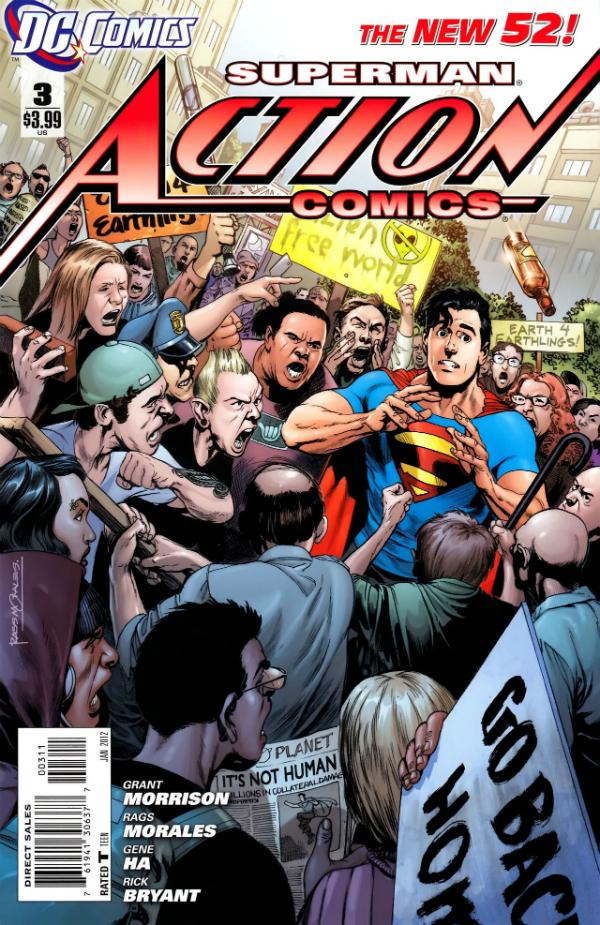

Superman the immigrant

Consider Paul Verhoven’s Robocop, and its satirising of ’80s corporate culture and free-market neo-liberalism; the long-running TV series Babylon 5 and its take on religious fundamentalism and 20th-century international relations; 1956’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers and its commentary on McCarthyism; Romero’s Dawn of the Dead skewering mindless consumerism; the 21st century reboot of Battlestar Galactica tackling military occupation and insurgency only a few years into the Iraq war; and the abstract yet poignant ruminations of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker on humanity’s search for spiritual enlightenment and ultimate meaning. In print, too, a tradition exists in SF of allegory, metaphor and commentary on goings-on in the real world. The most famous examples are probably Orwell’s 1984 and Huxley’s Brave New World, both of which envision nightmarish dystopias as the inevitable consequence of real-world trends in the politics and society of their authors’ time, but there’s also Orson Scott Card’s modern classic Ender’s Game, which deals with child soldiers and the dangers of simulated warfare (decades before drone strikes became a regular component of modern army tactics), and more recently China Mieville’s Embassytown and its thinly-veiled critique of British colonialism, to name just a couple of many possible examples. Marvel’s X-Men comics have consistently dealt with issues of intolerance and alienation since their inception, and the origin story of Superman, the most iconic superhero of all, has long been interpreted – at least in part – as a comment on immigration, an element made particularly explicit in Grant Morrison’s recent Action Comics run. Even in gaming, we see science fiction making statements about the real world, not least with 2007’s Bioshock, which dealt with the moral philosophy of objectivism which still inspires political movements today, and its 2013 sequel Bioshock Infinite, which concerns (among myriad other themes) the legacy of America’s 19th-century wars and the insidious nature of historical revisionism. These are just a few examples, across multiple media, of works of science fiction making comments on, or relating to, so-called “real world” issues. The list could go on and on, such is the rich heritage of this theme within the genre.

Bioshock Infinite’s American dreamscape

Despite its unrealistic setting, then, science fiction can obviously be all about the “real world”, but why is this so frequently the case? As the (by no means exhaustive) list above shows, SF authors, artists and film-makers regularly create stories which take inspiration from events in the non-fictional realm, and have been doing so for a very long time. Is this simply due to a dearth of original ideas in the genre, or might there be another reason for it? I suspect that the reason allegory and metaphor so regularly appear in SF works is that the genre as a whole is actually an incredibly effective context in which to discuss the “real world”.

Chronicling historical and contemporary world events as a matter of documentation is all well and good; a well-made documentary about the civil rights movement or a well-written book about the Iraq war will be informative, well-researched and (hopefully) relatively impartial, and will serve to educate people about important figures and events in world history. But to provoke deeper thought about such issues on the part of an audience, it can in fact be more effective to approach the subject indirectly. Being exposed to true stories of landmark events and figures via the medium of print or screen can in fact make these real-world occurrences seem slightly ‘unreal’ to the reader/viewer, because although the experience can enlighten and inform them, it can also have a distancing effect, as it tries to represent concrete reality through an inherently abstract medium. Reading about the holocaust, for example, will make you informed about the historical facts of the matter, but attempting to then hold in one’s mind the idea that a horrific tragedy of such magnitude actually happened in our own recent history is another matter. Embedding echoes of real-world events in an unrealistic setting (as SF allegories do) actually makes the elements inspired by our own history and experience stand out all the more. A sort of resonance occurs which causes us to think more deeply about these figures and events from the “real world”, precisely because we have encountered them in an indirect fashion, devoid of the distancing effect of head-on documentation. It is in this way that science fiction (and indeed fantasy and horror, too) can not only be all about the “real world”, but can in fact be a very effective way of talking about it.

To be continued in part two, which will look at surreality and weirdness as indirect paths to truth….

[…] the real world and/or grappling with the big ideas of religion and philosophy. As was the case in part one of this article, this will show why an artistic style often considered to be totally divorced from […]