The Voynich manuscript (so called) is one of the most profound mysteries in the history of literature. Believed to have been written in the 15th century, it appears to be rendered in an entirely artificial language and is illuminated with strange drawings, the nature of which ranges from the biological and pharmaceutical to the astronomical and cosmological. There is no clear consensus amongst scholars as to who authored the manuscript, why they did so, and what its real purpose and meaning might be. The as-yet undiscovered truth about the work is probably completely mundane, but it’s extremely tempting to think that the unlocking of its secrets might reveal the answer to some deep, cosmic mystery about life, the universe and everything. Such a reaction is partly due to human beings’ innate desire to seek meaning and structure wherever there appears to be none, but it is also because, particularly throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, works of weird or surreal art which appear devoid of any conventional meaning have – ironically – often been the most effective way to communicate profound ideas which grapple with grand themes like religion, ethics and metaphysics.

Dali’s ‘The Persistence of Memory’

Surrealism as an artistic trend grew out of the Dada movement of the early 20th century, and although the Dadaists’ reactionary opposition to reason and logic meant that their work was largely devoid of any coherent, deeper meaning (that is, if having no meaning cannot in itself be considered a sort of meaning), Surrealism from its earliest days in the 1920s was considered, by contrast, to be a force for societal change, inspired partly by the theories of Karl Marx and G.W.F. Hegel. Surrealists strove to liberate the imagination and give expression to the unconscious by breaking away from historical conventions in art and literature. They used dream logic, unexpected juxtapositions and nonsensical concepts to achieve these ends, leading to myriad works of written and visual art which often seem confusing, disorientating and somewhat unsettling. But there was frequently a deeper meaning to be found beneath the illogical facade, one which could be represented all the more effectively by being divorced from suffocating artistic convention. Andre Breton – one of the key figures in early Surrealism – saw his technique of ‘automatic writing’ through a Marxist lens, believing it to be a way of circumventing the shackles into which writers and artists had been socialised by the bourgeois elite; the artist Salvador Dali’s eerily contorted imagery was at least in part a reflection of his anarchist principles and his consequential rejection of authority and convention; Rene Magritte’s severance of everyday objects from their familiarly banal context forced viewers to contemplate the nature and essence of those objects and their symbolic representations; and in the work of Surrealist film-maker Luis Bunuel we find – despite his best efforts to avoid any kind of coherent, deeper meaning – a running critique of organised religion.

Magritte’s ‘The Liberator’

These were the eccentric minds that gave birth to a movement, but despite its nonconformist tendencies Surrealism as a style has retrospectively become absorbed into the artistic mainstream, with Dali and Magritte’s paintings adorning walls in populist galleries everywhere, and Brunel’s films widely considered a landmark in the history of cinema. The subversive influence of these surrealist pioneers persists, however, and has been seeping into popular culture for decades, thanks to a raft of writers, artists, film-makers and musicians who have picked up the baton and set about creating myriad works which not only defy traditional logic and artistic convention, but also deliberately utilise this approach to communicate deeper meanings and profound ideas through their apparently meaningless art.

My objective here is not to provide an exhaustive list of surrealist pop-culture works of the last 50 years, but rather to illustrate the argument that surrealism can very effectively communicate deeper meaning and truths about the real world by using examples from modern pop-culture. To that end, I shall look at a number of surrealist works from film, literature and music and then consider why they have succeeded so effectively in making statements about the real world and/or grappling with the big ideas of religion and philosophy. As was the case in part one of this article, this will show why an artistic style often considered to be totally divorced from reality actually provides a very effective way to talk about it.

‘El Topo’

Alejandro Jodorowsky’s mind-bending surrealist western El Topo (1970) makes an excellent starting point, illustrating as it does the director’s desire to tackle grand themes in an indirect fashion with a memorable opening statement: “The mole digs under the earth looking for the sun. Sometimes, he gets to the surface. When he sees the sun, he is blinded.” The film’s bizarre plot, which eschews conventional narrative structure, makes strong statements about religion and pacifism through the story of a violent gunslinger who undergoes a strange transformation and becomes the spiritual leader of a band of outcasts and misfits. Rather than making these statements explicitly, Jodorowsky allows deeper meaning to emerge from sequences of jarringly peculiar imagery, a technicolor fever dream which ultimately becomes a search for divine truth. We, he is saying, are moles digging in the dirt to find the sun, because to look directly at it would be blinding. David Lynch, a similarly surrealist auteur, uses an array of nightmarish scenes in his 1977 debut Eraserhead to explore the suffocating, dehumanising bleakness of America’s industrial wastelands, as well the intense anxiety of first-time fatherhood, without resorting to tackling these themes head on.

‘Eraserhead’ – the dehumanising bleakness of industrial America

Notorious British film-maker Alex Cox (Repo Man, Sid and Nancy) uses surrealism potently in his unfairly-derided 1987 film Walker, which transplants deliberate anachronisms such as cars, lighters, magazines and guns from the 1980s into the setting of mid-19th century Nicaragua, the method in his madness being a reminder that US intervention in Latin America (Walker was filmed during the Contra War) was nothing new, and had in fact been going on for more than a century. A more recent example is Nicolas Winding Refn’s Only God Forgives, a film which also attracted much critical derision upon release, despite its many virtues. Explicitly influenced by the work of Jodorowsky, Refn’s film, as we have previously examined, tackles humanity’s capacity for evil as well as meditating on the theme of redemption, using brutally violent imagery and jagged, dream-like storytelling.

Johnson’s ‘The Unfortunates’ – mimicking the randomness of human memory

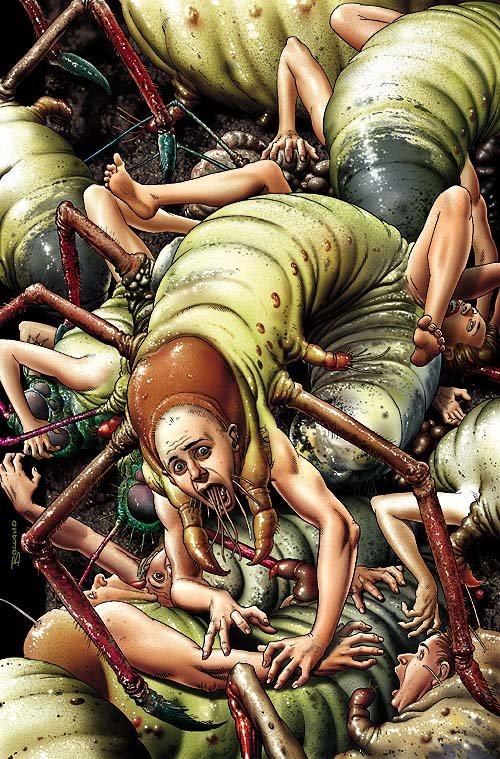

In literature, too, surrealist techniques have frequently been used over the last half century to engage with big ideas and real world experiences. Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Paramo, widely considered to be the first magic realist novel, features non-linear narrative and bizarre characters in a story which ultimately concerns historical injustice and the nature of truth. The modern classic Lanark, written by Alasdair Gray, uses a surreal and distorted mirror-image of Gray’s home city of Glasgow as a setting in which to engage with topics as diverse as unrequited love, life after death, suffocating bureaucracy and the terrors of aging. B.S. Johnson’s 1969 cult novel The Unfortunates was published not as a bound tome, but as a collection of individual chapters which could be read in any order – an attempt by Johnson to convey the randomness of human memory – while another formally experimental book, Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves, uses disorientating page layouts, multiple layers of narrative and what appear to be frequent non sequiturs in a story which concerns, among myriad other things, humanity’s cosmological insignificance and the subjectivity of all experience. Grant Morrison’s epic comic book sagas The Invisibles and Doom Patrol frequently use surreal imagery to convey the mind-shattering experience of characters encountering time travel, the end of the world, child abuse, madness and death.

This is what space-time looks like – ‘The Invisibles’ (1998)

Throughout 20th century music, too, there are a number of examples of artists using the surreal to communicate deeper meaning through their work. The most obvious example is the free jazz movement, which arguably began with the late ’50s recordings of Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor before developing into a fully-fledged musical philosophy by the mid-’60s, particularly through the later work of John Coltrane. Eschewing conventional structures, rhythms and harmonies, free jazz usually features collective improvisation with little or no set score, resulting in pieces of music characterised by jarring atonality, continuously evolving ideas and/or formless, floating serenity. Free jazz artists’ long association with the civil rights movement meant that many of these confrontational works would become imbued with a deeper meaning, their cacophonous onslaught mirroring the tumultuous struggle for racial equality in ’60s America, but much of this weird and wilfully difficult music was created with specific themes in mind, its creators using the form’s liberating obtuseness to communicate ideas on a grander, more profound level. Coltrane’s Ascension, Pharoah Sanders’s Karma and Albert Ayler’s Spiritual Unity are all albums which explore themes of religion and spirituality by eschewing conventional musical structures for the chaotic frenzy of improvised sound, and in doing so attain an unknowable, otherworldly quality which befits their ambitious subject matter.

“Damn the rules, it’s the feeling that counts” – John Coltrane

Surreality has also been used by many musicians in their lyric writing, resulting in a peculiar poetry which bears all the hallmarks of classic surrealist literature. Frequently these rambling lines of free association and startling imagery conceal thinly-veiled deeper meanings; consider Genesis’ 1974 album The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, an epic story of crime, lust and redemption described through a bizarre mixture of mythological symbolism and blackly comic grotesquery, or the work of the late Captain Beefheart, littered as it is with examples of songs which, despite their seemingly impenetrable weirdness, deal with heavy subjects like war, poverty and the holocaust. One of the Captain’s most poignant tracks is the ludicrously-titled 81 Poop Hatch, a spoken word piece made up of fragmented day-to-day observations from which emerge an overwhelming sense of weariness and emotional struggle, feelings which Beefheart could perhaps not have conveyed so acutely had he relayed them in more conventional, straight-talking lyrics. These are just a couple of examples, and there are many more, but they serve to demonstrate how the tropes of surrealism have been put to use by the musicians of the late 20th century.

Captain Beefheart

So what is it that unites these disparate examples of popular culture from a diverse range of media? Simply put, they all utilise the techniques of surrealism – dream logic, unexpected juxtapositions and nonsensical imagery – not just to liberate the imagination, but also to direct it. Each work approaches a theme or idea of profound emotional, political, philosophical or religious significance in an indirect, tangential way, shearing away the tropes of convention to afford a fresh and enlightening perspective on thought-provoking ‘big ideas’. Whether it be Alex Cox’s ruminations on American foreign policy, B.S. Johnson’s portrayal of human memory or John Coltrane’s expression of love and gratitude to a divine creator, the complexity or abstract nature of the subject matter demands, in the minds of these creators, an artistic approach which diverges from convention in the most radical way. But why not tackle these issues head on, if they are considered so important? Surely a simpler, more direct approach will result in greater clarity of meaning if a statement is to be made by the artist in question?

Not so, say the surrealists, and the counterargument is two-fold: firstly, the structures, techniques and conventions of any artistic medium become stale and cliched over time, rendering the possibility of a truly fresh approach within the confines of tradition remote at best. A version of this argument was made by Andre Breton in the early 20th century, when he suggested that the conventions of literature had not only become stale, but also a tool of bourgeois oppression; writers had been socialised into working within this predetermined structure to ensure that they could never write anything truly radical or revolutionary. Whether or not one lends credence to Breton’s class-based theory, it’s hard to deny that getting bogged down in convention curtails artistic possibility, and can contaminate any artist’s study of political, social, religious or philosophical ideas with a stale artificiality, hampering the communication of meaning.

Secondly, and more importantly, it can be argued that the structures and techniques conventionally associated with particular art forms (e.g. linear narrative in literature and film, realistic juxtaposition in visual art), were never sufficient to tackle truly grand themes in the first place. Why should this be so? Humans construct meaning to understand the world around them, and conventional story-telling, where effect follows cause and everything has a beginning, middle and end, is a simple, rational way to make sense of our lives, loves, actions and place in the universe. It is, however, a poor way to grapple with ideas whose content stretches beyond conventional understanding, whether because of socialising factors or simply the limits of the mind. As one approaches a theme like the nature of God, the experience of remembering, the possibility of objective truth or the veracity of history, conventional structures can become a prison for the artist, because man-made constructs by definition cannot hope to encompass those things that probe at the limits of our understanding. We cannot, to use Jodorowsky’s metaphor, stare at the sun; instead, we must dig for it. And we dig by breaking away from the shackles of convention, abandoning the rigid concepts which determine our everyday reality so that we may glimpse something far bigger than ourselves.

This is the reasoning which underpins the politically and philosophically-charged work of many pop-culture surrealists, and from their apparently meaningless films, books and music emerge deeply meaningful meditations on grand ideas, their pursuit of which must be deliberately circuitous. In this way, appearing to be devoid of meaning actually becomes the best way to communicate it, and just as we always invent to remember, so they obscure to reveal.