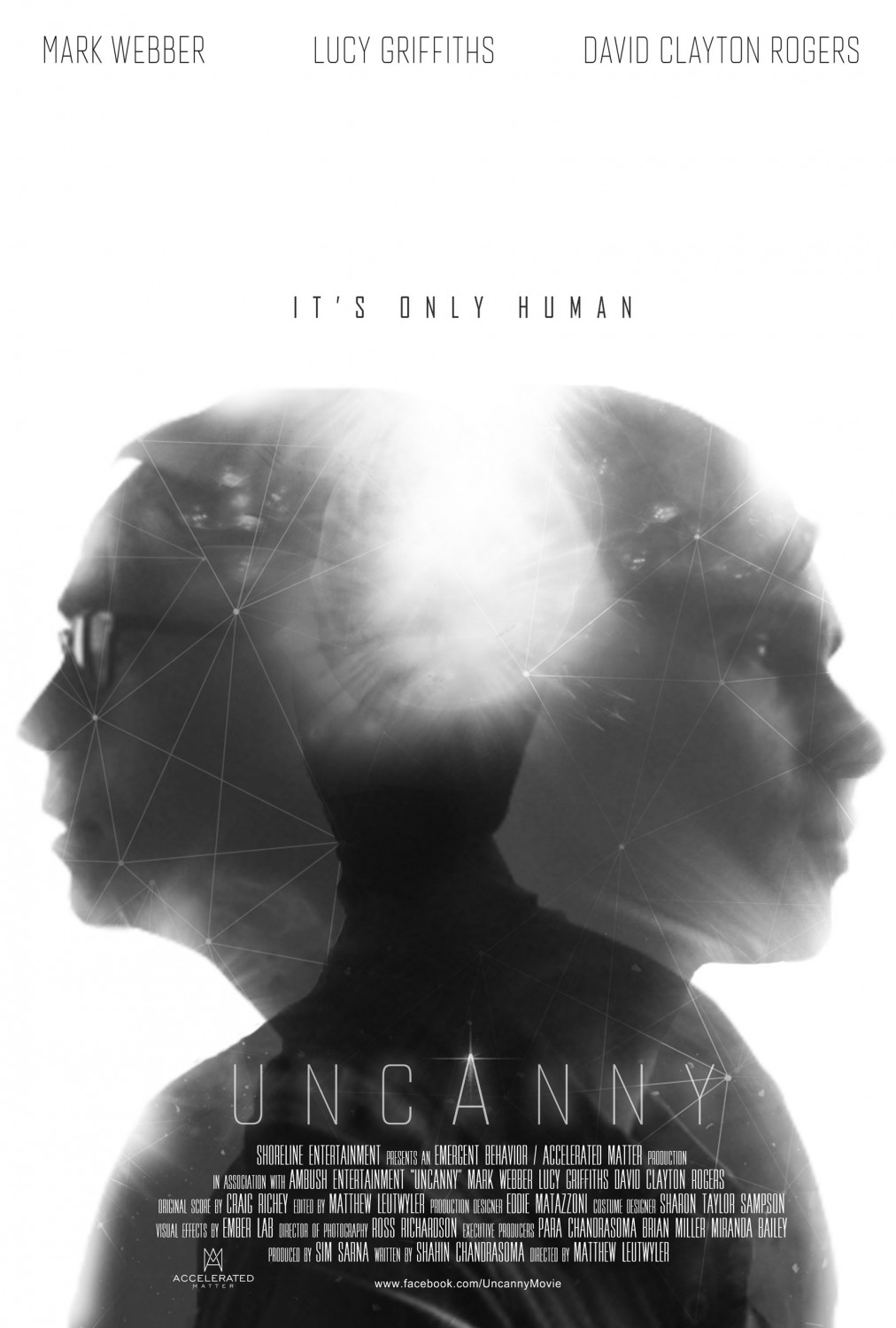

The extent to which an emergent artificial intelligence might resemble a human being has driven the narrative of countless science fiction films, with mankind’s fate often hinging on just how ‘human’ such an entity turns out to be. Matthew Leutwyler’s Uncanny (which received its UK premiere at last month’s Edinburgh International Film Festival) is also concerned with this question, but unlike most of its predecessors shifts this idea of reflective humanity from the realm of the intellectual to the emotional. By focusing on a machine’s capacity for emotion rather than just sentience, Leutwyler and screenwriter Shahin Chandrasoma pose fundamental questions about what it really means to be ‘human’, and whether an AI could be more so than some actual human beings.

Frustrated tech journalist Joy (Lucy Griffiths) gains exclusive access to the world’s first authentic artificial intelligence, an android named – appropriately – Adam (David Clayton Rogers) who has been shut away in an isolated lab run by the shadowy Mr Castle (Rainn Wilson in the briefest of cameos). Over the course of 7 days, Joy’s initial skepticism gives way to fascination as her passion for science is reawakened by Adam’s creator David (Mark Webber), a man with whom she begins to develop a bond that goes beyond professional curiosity. What none of them can foresee, however, is the effect that Joy’s presence in the lab will have on the relationship between creator and creation, and as Adam struggles with new-found emotions beyond his understanding, his behaviour starts to become increasingly threatening.

With its small cast, isolated location and preoccupation with AI, comparisons between Uncanny and Alex Garland’s Ex Machina are perhaps inevitable. But while Garland’s film takes a somewhat cynical view of human-AI relationships and makes manipulation its main theme, Uncanny is far more neutral in its depiction, and focuses on those unpredictable, emergent traits immune to advance calculation, namely emotions. If emotions are the essence of humanity, Chandrasoma seems to be saying, then what does it mean when a machine becomes more emotional than a human being?

The film’s claustrophobic setting serves both to keep our attention fixed on the developing character relationships, and to amplify the tension which emerges when Adam’s interest in Joy takes on a decidedly creepy dimension. At times the latter half of Uncanny feels like a horror movie, but the film never fully slips into that genre, remaining instead an intriguing study of both human and non-human characters. Low-budget/high-concept science fiction films live or die by the strength of actors’ performances, and luckily none of Uncanny‘s three leads are anything less than superb, especially Rogers, whose role demands much delicate complexity.

It’s a shame that the film sabotages itself with some jarringly unnaturalistic dialogue in the first half hour, and a wealth of religious symbolism which, while occasionally profound, becomes increasingly heavy-handed. Its attempt to portray the human cost of morally-unfettered scientific advancement is also awkwardly undermined by a mid-credits scene which undoes a lot of hard work for a cheap cliffhanger, and shies away from tackling some very controversial issues raised by earlier events. These shortcomings blight an otherwise beguiling film which, despite its superficial resemblance to Ex Machina, feels like it genuinely has something fresh to offer in terms of storytelling, and suggests that maybe it’s emotions, and not intelligence, that our future creations will reflect back at us most clearly.

There is currently no UK-wide release date for Uncanny.