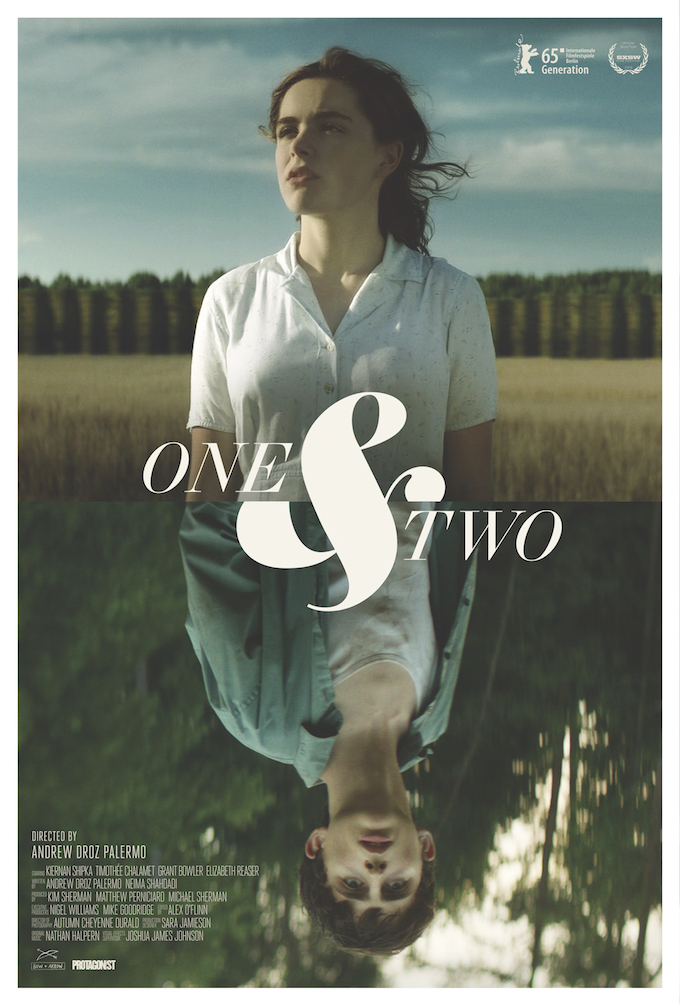

It feels tremendously reductive to call Andrew Droz Palermo’s One & Two an alternative take on the superhero origin story, but it also says a lot about the omnipresence of caped crusaders in modern popular culture that the comparison still seems an apt one. While not as abstract as Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu’s Birdman, One & Two shares its gray-shaded position of being a film which is inspired by superheroes (or reacts against them), but is not itself a superhero film. Really it’s a story about growing up different, the fear that difference inspires, and the love that can tear families apart but also make them whole again.

Siblings Zak and Eva (Interstellar‘s Timothee Chalamet and Mad Men‘s Kiernan Shipka) live with their parents on what appears to be a 19th century homestead, peacefully working the land as the years roll by. Cut off from the outside world by a gigantic, impenetrable fence, brother and sister dream of one day escaping to distant lands, spurred on by the sight of the airplanes that frequently pass overhead. Their only real source of joy is a shared ability to teleport, something forbidden by their devoutly religious father who believes this power to be blasphemous and the cause of their mother’s rapidly deteriorating ill health. Grief, fear and rage run amok as the children begin to test the many barriers erected around them, and start to grasp some unpleasant truths about humanity’s capacity for intolerance.

Palermo infuses One & Two with a dream-like atmosphere right from the very beginning, and his mixture of hazy visuals and warped logic is ultimately central to the film’s appeal. The nightmarish, impossible barrier surrounding the family’s homestead is the stuff of fairy tales, and although its origin is hinted at we’re never really told who built it or why. Together with the jarring sight of modern aircraft crossing the sky above a motor-free farmhouse, this is an early sign of the peculiar sense of unreality which pervades the film even in its starkest moments of grim family drama. The nature of the children’s power is also ambiguous; it allows them to teleport anywhere in their line of sight, but how they’ve come to possess it and whether it might truly be related to their mother’s debilitating illness remains uncertain.

It’s their father’s inability to live with that uncertainty that drives a brutal story of misplaced anger and willful ignorance, and the scenes where he clamps down on his children’s behaviour are both harrowing and rife with religious symbolism. The idea of family members shunning super-powered relatives is one that’s been explored before, often as a heavy-handed allegory by the various incarnations of Marvel’s X-Men, but rarely has it been done with such unpleasant tension. The performances of all four leads are compelling, and provide the foundation upon which Palermo’s haunting story rests. Shipka in particular is excellent, playing Eva as the emerging moral compass of the family, much to her and her brother’s cost. Although at times the film’s story feels a little too slight for its 90 minute running time, and there are a few scenes where the narrative is stretched thin, One & Two turns out to be a moving little film that explores several of the more sensitive issues raised by superhero stories, but without having to adhere to any of the tropes of the genre.

There is currently no UK-wide release date for One & Two.